What are you afraid of? Me, I’m fairly OK with bugs and creepy crawlies but I can’t last five minutes into most horror films. We all have our own personal fears Read more

Science, Curiosity and Life

What are you afraid of? Me, I’m fairly OK with bugs and creepy crawlies but I can’t last five minutes into most horror films. We all have our own personal fears Read more

I watched a great documentary on Netflix* recently all about lying… it is called Dis(honesty): the truth about lies and I would highly recommend it.

It really got me thinking about lying, why do we do it, what would happen if we don’t and is it a uniquely human activity?

First off, we all do it! If you are shaking your head in disagreement, then you’ve just lied too! Sometimes we do it for good reasons, sometimes just to save our skin, but we all lie from time to time. So why do we do it and is it a purely human activity?

We lie for a number of reasons, it may be a little white lie to make someone feel better or it might be a big lie for our own gain, or to save our skin!

Many of the lies we tell are to present a better side of ourselves; make ourselves appear a little nicer, a little smarter, or a little more popular. We don’t often even recognise these lies, we don’t realise we are doing it – we are lying to ourselves!

On a base level, we probably lie because evolution has shown us that it works to our benefit and the benefit of society. As our social connections have developed, so too have our abilities at lying. It is actually a valuable tool to have and brings with it many advantages. Lying is a sign of intelligence and is considered a complex cognitive skill.

There are different types of lies and different categories of liars! There are the little white lies that we all do, usually for social acceptance or compliance. There are lies of exaggeration, usually of little harm either; and then there are the bigger lies that are often more serious and come with a lot more consequences if found out.

There are also different types of liars. We are all contributors to the pool of common-or-garden, everyday liars, but things get more serious when we look at the compulsive or pathological liar.

Compulsive liars tell lies as the norm, it is an automatic reflex and it takes a lot less effort for them than telling the truth does. Pathological liars tend to take it one step further; they lie for their own gain, with little thought to the consequences of their lies, for either themselves or others.

Lying is a complex process; in order to do it our brains must focus on two opposing pieces of information at the same time: the truth and the lie. If we want to process or deliver a lie we need to believe that it could be true. The brain has to work much harder to lie than to tell the truth. Activity in the prefrontal cortex (at the front of the brain) has been shown to increase when a person lies. This is the part of the brain involved in decision making, cognitive planning and problem solving.

Usually when we tell a small lie, for personal gain, we feel bad. These emotions of regret and guilt are controlled by a part of the brain called the amygdala. However, the more we lie, the more we desensitize the amygdala so that it produces less of these bad feelings.

Studies on the brains of pathological liars show that they have about 25% more white matter in their prefrontal cortex, suggesting more connections between different parts of the brain. However, they also have about 14% less grey matter, the part that can help rationalise the potential consequences of each lie told.

No man has a good enough memory to be a successful liar- Abraham Lincoln

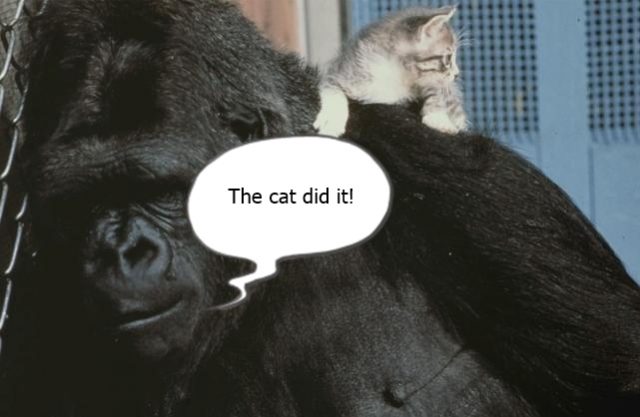

Yes some do. One famous example that my children love to hear about is of Koko the gorilla. Koko is renowned for her sign language abilities, with an impressive vocabulary of more than 1000 words. Koko has a pet kitten that has come in handy for more than just cuddles and companionship. One day Koko tore a sink from a wall in her enclosure. When her carers returned and asked what happened, Koko signed ‘the cat did it!’

Some scientists believe that we begin the act of deception as young as six months old! This usually starts as fake crying, or smiling, to get attention. At that age we don’t do a very good job (although it is probably quite cute and amusing to watch) and we likely do not do it as a conscious lie.

By the age of two however, we have put in a little more practice and can deliver an outright lie with more commitment and conviction.

Adults are so good at lying that they can often lie even to themselves; on average, adults lie about 10 times a day and we can throw about three lies into a short conversation with a stranger, without even knowing we are doing it.

Some of us are better liars than others and there is no detection system, including lie detectors, that work for all. However, many of us amateurs give away some tell-tale signs when we are lying, such as…

Interestingly, we are better at lying when we lie for altruistic reasons than for our own good and these lies are more difficult to detect.

So that is the low-down on lying, and not a word of a lie 😉

Have you any facts or stories to add? I’d love to hear them, just leave them in the comments below.

*Disclosure: As a member of the Netflix Stream Team I have received a years subscription to Netflix, free of charge, and an Apple TV, for streaming purposes. As part of Netflix Stream Team I will be posting monthly updates on what we are watching and what is on offer. All opinions expressed will be my own.

I was chatting with my son the other evening when he stopped for a second and said… “you know I really feel like we had this exact conversation before, sitting here, in the exact same way… and that happens to me a lot”.

Time to explain déjà vu.

First off, it is a phenomenon that most of us have experienced. Understandably, it is not an easy thing to study; it tends to happen rarely, is very brief (the feeling usually last between 10 and 30 seconds) and is usually unpredictable. So unless we all walk around with wires stuck to our head, it is a hard one to monitor.

Before looking further into the study of déjà vu, or explanations as to how it works, a definition is required.

Déjà vu is a French term, coined in 1903 by French scientist Émile Boirac and meaning “already seen”. It describes the sense that you have already experienced a current event. It is a sensation that is happening in real time… you are feeling it during, not before, the event so it is not a predictive sense.

Here is an example… you have travelled to a new city for the first time and, as you sit outside a café, listening to your friend talking and feeling the sun on your face you get that very strong feeling that you have lived this exact experience before. And yet you know you have never before been to that café, in that city, with that friend.

So when does déjà vu happen?

It can happen anytime, anywhere. Some people say it happens frequently, some not at all. Through survey and analysis of defined groups the data suggests that people have their first experience of déjà vu between the ages of six and ten, that it is most common among 15 to 25-year-olds and that the occurrence tends to taper off after that.

Of course the first experiences in the six or older bracket could also be explained by a sufficient cognitive ability to recognise and verbalise the sensation, perhaps not present in younger children. Why does déjà vu appear to reduce after the age of 25? It is suggested that this may just be that people become less intuitive or aware of the signs and sense of déjà vu as they age. So a higher frequent of the experience could suggest a heightened awareness and analysis of environment and feelings.

How is déjà vu studied?

As mentioned above, there are a few difficulties in studying the phenomenon of déjà vu; One direct method is with questionnaires and study groups. With something like déjà vu of course, the answers are very subjective.

More direct study methods, have been carried out by Anne Cleary, professor of cognitive psychology at Coloroda University. Initial studies tested to see if images with familiar links could trigger a memory response, even when the link is not obvious. These studies included looking for familiarity triggers in people shown a series of words, some of which had similar sounds. In other studies, volunteers were shown lists of celebrity names and then a variety of celebrity photographs. They were then asked to indicate which celebrities in the photographs were among the list of names originally shows. Interestingly, a large number of volunteers were able to correctly answer these questions, even when the celebrities and their names were not obviously known to them.

Cleary and her team moved on to more complex test methods looking for déjà vu type responses triggered by 3 D computer simulated scenes, appropriately named Déjà ville.

The study group donned computerized headsets that immersed them in a sequence of 3D scenes. The scene layouts appeared unique, however, certain ones contain geometric shapes, like a chair, placed at the exact same grid reference as previously seen in another sample. The scenes with the repeat spatial element tended to trigger feelings of familiarity.

More physical methods of studying déjà vu focus on tracking brain activity with either direct methods like an Electroencephalography (EEG) or indirect methods, like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The unpredictable nature of Déjà vu makes this type of study difficult. However, these methods have been applied to two specific groups of people who have a more frequent or predictable form of Déjà vu.

One such group – chronic suffers of déjà vu, are part of a study currently being conducted at a memory clinic at the University of Leeds.

Another group consists of patients with a specific type of epilepsy (medial temporal lobe epilepsy) that affects regions of the brain associated with memory. These regions include…

People with temporal lobe epilepsy often report a déjà vu like experience directly before a seizure. In studies where this process is triggered by electronic stimulation, an increase in neuronal firing in the hippocampus and amygdala have been reported.

How does déjà vu work?

The short answer is that the exact mechanisms and triggers of déjà vu are unknown, but here are some suggestions based on current research:

Do you have any interesting déjà vu stories or have any different suggestions to add?