I watched a great documentary on Netflix* recently all about lying… it is called Dis(honesty): the truth about lies and I would highly recommend it.

It really got me thinking about lying, why do we do it, what would happen if we don’t and is it a uniquely human activity?

First off, we all do it! If you are shaking your head in disagreement, then you’ve just lied too! Sometimes we do it for good reasons, sometimes just to save our skin, but we all lie from time to time. So why do we do it and is it a purely human activity?

We lie for a number of reasons, it may be a little white lie to make someone feel better or it might be a big lie for our own gain, or to save our skin!

Many of the lies we tell are to present a better side of ourselves; make ourselves appear a little nicer, a little smarter, or a little more popular. We don’t often even recognise these lies, we don’t realise we are doing it – we are lying to ourselves!

On a base level, we probably lie because evolution has shown us that it works to our benefit and the benefit of society. As our social connections have developed, so too have our abilities at lying. It is actually a valuable tool to have and brings with it many advantages. Lying is a sign of intelligence and is considered a complex cognitive skill.

Different types of lies and liars

There are different types of lies and different categories of liars! There are the little white lies that we all do, usually for social acceptance or compliance. There are lies of exaggeration, usually of little harm either; and then there are the bigger lies that are often more serious and come with a lot more consequences if found out.

There are also different types of liars. We are all contributors to the pool of common-or-garden, everyday liars, but things get more serious when we look at the compulsive or pathological liar.

Compulsive liars tell lies as the norm, it is an automatic reflex and it takes a lot less effort for them than telling the truth does. Pathological liars tend to take it one step further; they lie for their own gain, with little thought to the consequences of their lies, for either themselves or others.

What happens in our brains when we lie?

Lying is a complex process; in order to do it our brains must focus on two opposing pieces of information at the same time: the truth and the lie. If we want to process or deliver a lie we need to believe that it could be true. The brain has to work much harder to lie than to tell the truth. Activity in the prefrontal cortex (at the front of the brain) has been shown to increase when a person lies. This is the part of the brain involved in decision making, cognitive planning and problem solving.

Usually when we tell a small lie, for personal gain, we feel bad. These emotions of regret and guilt are controlled by a part of the brain called the amygdala. However, the more we lie, the more we desensitize the amygdala so that it produces less of these bad feelings.

Studies on the brains of pathological liars show that they have about 25% more white matter in their prefrontal cortex, suggesting more connections between different parts of the brain. However, they also have about 14% less grey matter, the part that can help rationalise the potential consequences of each lie told.

No man has a good enough memory to be a successful liar- Abraham Lincoln

Do other animals lie?

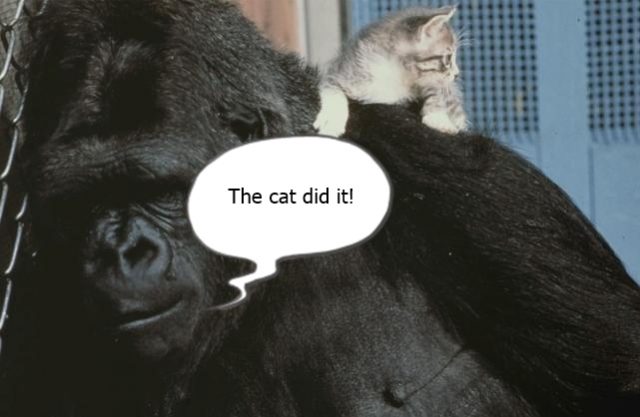

Yes some do. One famous example that my children love to hear about is of Koko the gorilla. Koko is renowned for her sign language abilities, with an impressive vocabulary of more than 1000 words. Koko has a pet kitten that has come in handy for more than just cuddles and companionship. One day Koko tore a sink from a wall in her enclosure. When her carers returned and asked what happened, Koko signed ‘the cat did it!’

When do we start lying and how often do we do it?

Some scientists believe that we begin the act of deception as young as six months old! This usually starts as fake crying, or smiling, to get attention. At that age we don’t do a very good job (although it is probably quite cute and amusing to watch) and we likely do not do it as a conscious lie.

By the age of two however, we have put in a little more practice and can deliver an outright lie with more commitment and conviction.

Adults are so good at lying that they can often lie even to themselves; on average, adults lie about 10 times a day and we can throw about three lies into a short conversation with a stranger, without even knowing we are doing it.

Are there ways to spot a lie?

Some of us are better liars than others and there is no detection system, including lie detectors, that work for all. However, many of us amateurs give away some tell-tale signs when we are lying, such as…

- We make and keep direct eye contact (contrary to common held belief)

- We keep our bodies very still, but we may…

- jerk our heads a lot

- We give more information than is necessary

- We touch or cover our mouths with our fingers

- We breathe at a more rapid rate

- We cover vulnerable parts of our bodies, such as the throat, head or chest

Interestingly, we are better at lying when we lie for altruistic reasons than for our own good and these lies are more difficult to detect.

So that is the low-down on lying, and not a word of a lie 😉

Have you any facts or stories to add? I’d love to hear them, just leave them in the comments below.

*Disclosure: As a member of the Netflix Stream Team I have received a years subscription to Netflix, free of charge, and an Apple TV, for streaming purposes. As part of Netflix Stream Team I will be posting monthly updates on what we are watching and what is on offer. All opinions expressed will be my own.